“Buy on the sound of cannons, sell on the sound of trumpets.”

We owe this wise and winged investor’s phrase to the legendary financier Nathan Rothschild, who, according to tradition, made a fortune during the Napoleonic Wars. With the phrase, Rothschild is suggesting that the beginning of a war is a good time to buy shares, because investors overreact to the negative impact of the threat of war. And those same investors subsequently overestimate the positive effects of the end of the war, leading to excessively high prices and thus a potential selling point. But is Baron Rothschild right? Now that the markets are spellbound by the growing threat of war in Ukraine, it is certainly worth testing Rothschild’s position against the historical evidence and examining the impact geopolitical tension has on markets.

Geopolitical conflicts come in many forms

It is not particularly straightforward, because there are all kinds of geopolitical conflicts that clearly differ in scope and their potential consequences.

Fortunately, large-scale military confrontations between larger countries are now less common than at the time of our Baron. Therefore, we only have a limited sample of events (1st and 2nd Gulf War, Vietnam, Korea, etc.) to study the impact of these types of conflicts on the market.

Sadly, there has been no shortage of more limited regional conflicts or civil wars. Syria and Yemen are still flashpoints today, but there have also been many seemingly forgotten conflicts in Africa and Central America. Closer to home, we had the Balkan Wars. And the long-drawn-out conflict in Afghanistan is also still fresh in our memory.

Lastly, we have seen numerous terrorist attacks, of which 9/11 was undoubtedly the most serious. But every major European city (London, Madrid, Paris and, of course, Brussels) has had its dose of violence to deal with in recent years. It goes without saying that those moments where geopolitical tension rose high without any actual confrontation must also be included in the analysis. The mother of all geopolitical threats that was able to be dismantled in the nick of time was the Cuban missile crisis (1962). But the memory is sometimes short. Who remembers that Trump posted another provocative tweet to Kim Jong-Un in early 2018, saying that “my nuclear button is a much bigger and more powerful one than his, and it works”?

Large-scale conflicts follow Rothschild

But what impact does all this geopolitical tension have on the markets? In 2015, researchers from the Swiss Finance Institute, a public-private partnership between Swiss banks, six universities and the Swiss federation, investigated all conflicts involving the US after WWII*.

And what did they find? Their conclusions are entirely consistent with Rothschild’s statement! Indeed, they discovered that stock markets experience a fall in the run-up to a conflict, but recover as soon as hostilities actually break out. However, when a conflict unexpectedly erupts, there is indeed a negative reaction on the stock exchanges.

Only, this correction also appears fairly short-lived: the stock market usually reaches its lowest point within three months of the conflict breaking out. For example, the market’s low point related to Saddam’s unexpected invasion of Kuwait (02/08/1991) was 71 days after the invasion, and was barely 23 days when the Korean War broke out (25/6/1950). The Swiss researchers themselves were rather surprised by their findings, and thus refer to it as “The War Puzzle”. Why, as Rothschild had noted, do investors seem to prefer a “safe” war to an “uncertain” risk of war? And why does the stock market recover so quickly when an “unexpected” war breaks out?

Stock market reactions to geopolitical tension depend on many factors

Various explanations are put forward for this, which relate both to the way in which conflicts affect investors’ choice parameters and to the influence of the conflict on the actual environment in which companies operate.

The threat of a large-scale conflict is a situation that is indeed difficult for investors to translate into a risk assessment for stock markets because it is a relatively “digital” phenomenon (war or no war?) with potentially far-reaching consequences. Faced with such uncertainty and the impossibility of performing a correct risk assessment, many investors therefore leave the stock market. Afterwards, the outbreak of war paradoxically becomes an event that reduces uncertainty, bringing us closer to the ultimate solution of the conflict, and thus a time to enter the market. Similar to this argument, some also point to the paradox of choice that an imminent conflict creates for investors with regard to their portfolio allocation. After all, it is clear that a peaceful solution to the conflict will favour other sectors than the outbreak of war. As long as it is unclear which of the two outcomes will transpire, it is a rational choice for investors to exit the stock market, and then, as soon as it becomes clear whether the conflict will end up peaceful or hot, to have the means to bet on the “right” sector horse.

But share prices don’t just capture geopolitical information. It is and remains extremely difficult to isolate the impact of geopolitical signals from all the other information. All the more so because geopolitical events will also steer other markets that are extremely important for share prices, namely interest rates and commodity markets. But besides that almost immediate market impact, geopolitical events will ultimately impact the real economy through the slower-acting channels of trade, capital flows and confidence. And because the “arc of tension” produced by geopolitical tension cannot by definition remain at its maximum level for long, over time the geopolitical signal will be increasingly displaced by traditional economic and profit parameters.

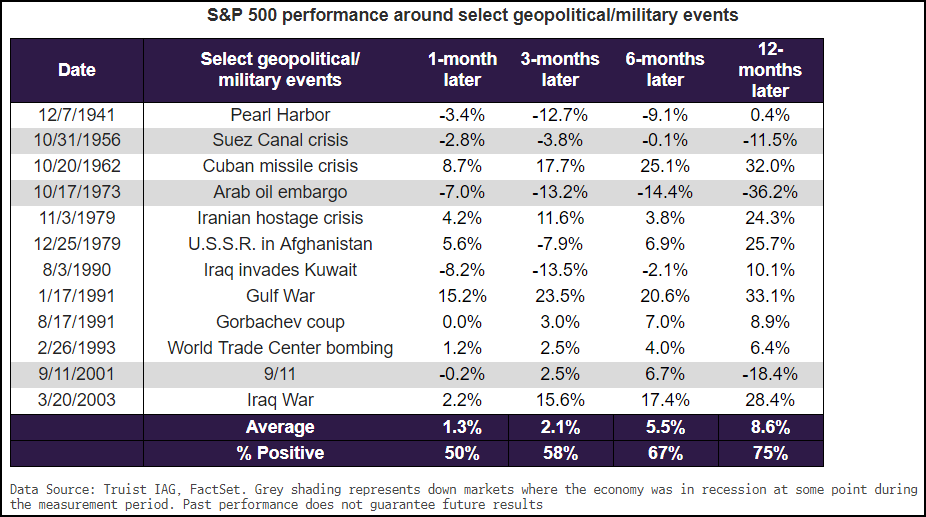

The following table clearly illustrates the impact of geopolitical events on share prices. In the vast majority of cases, the stock market recovers relatively quickly from the initial geopolitical shock, with its low point between one and three months after the panic. A year later, everything has long settled down, except in those cases where trust is so affected by the facts that it initiates a recession (grey rows in the table). Of course, it is always a question of retrospective interpretation as to whether the recession is actually the sole consequence of political and military tension, and whether that recession would have happened without that tension, i.e. whether the geopolitical shock was just that one nudge too far that pushed an already slowing economy over the edge of a recession.

Table: SP500 reaction to geopolitical events

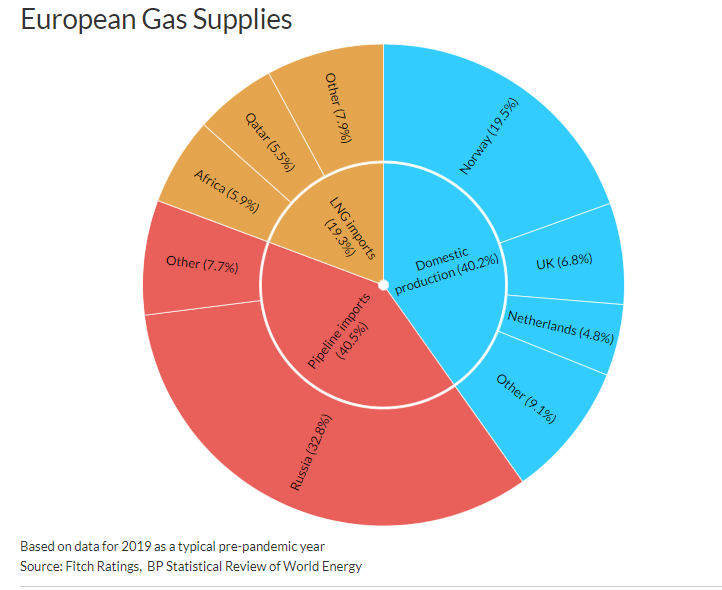

And it is precisely here that the problem lies with the markets: could the conflict involving Ukraine deteriorate into a recession, now that we have already had to deal with the headwinds of sharply rising inflation and the accompanying increases in interest rates, and the need to rein in out-of-control budget deficits after COVID-19? The big fear, of course, is that our energy supply may be at risk because Europe depends on Russia for about 1/3 of its gas supply.

European gas supply, 2019

What is often forgotten in the whole debate is that both Russia and Ukraine are also large exporters of grain. Western sanctions that would cut off grain supplies therefore risk contributing to a further rise in food inflation, at a time when inflation is already such a problem. In addition, Russia is an important supplier of phosphate and potash, basic materials for manufacturing fertiliser.

No one can, of course, predict whether it will really be open war. But if history teaches us anything, it is that in general, the impact of geopolitical conflicts is rather limited in magnitude, and that losses are recovered in the relatively short term. And even if the shock results in an economic downturn, it doesn’t have to be a disaster in the longer term for investors who stick to quality companies with robust balance sheets and high cash flow generation.

Christophe Van Canneyt

Senior Portfolio Manager

* “The war puzzle: contradictory effects of international conflicts on stock markets”, International Review of Economics, Vol. 62, No 1.2015